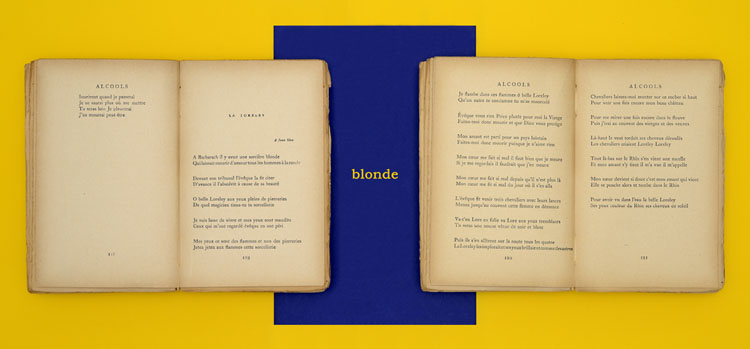

Apollinaire, Alcools

80 x 37 cm - 2012

L’interrogation de la page tournée

Le livre est photographié une deuxième fois, après avoir tourné une page, afin de montrer le poème dans son entiè- reté. Quand la lecture d’une page s’achève, avant qu’une autre vienne et que les mots recommencent plus tard, un moment de silence doit être traversé. Nous en avons peu conscience mais cet interstice reçoit la visite de notre esprit. Dans la composition, un espace mental s’ouvre en arrière-plan du livre et une autre page bleue apparaît. Projection du lecteur, elle est plus grande. L’espace d’un court instant, le lecteur peut y apercevoir la chevelure dorée de la sorcière de Bacha- rach, la Lorelei d’Apollinaire. La pensée du lecteur transperce l’éther bleu pour rejoindre ce qui se trouve en dessous et le mot « blonde » apparaît en lettres jaunes. Ainsi peut s’éta- blir un supplément d’affinité entre le lecteur et le poème. Guillaume Apollinaire fut un des premiers poètes à abolir la ponctuation. Il a placé l’intelligence entre parenthèses. Avant tout, il dit les élans du cœur et les désespérances qui les entraînent. L’amour, la mort. Le lecteur aborde le moment où la page est tournée sans avoir dû subir les coups de freins des points ou des virgules. Il est transporté par un flux inin- terrompu d’émotions dont la rémanence est d’autant plus grande pendant cette période qui précède la lecture des premiers mots de la page suivante. Voilà ce qui a justifié le choix de ce poète pour aborder cette idée d’une page bleue supplémentaire et invisible. La Lorelei qui inspire à Apollinaire l‘un de ses plus attachants poèmes est à l’origine une figure mythique du folklore germanique. C’est une nymphe des eaux, une nixe, une sorte de sirène qui envoûte les marins et les fait chavirer dans le Rhin. Dans la littérature du XIXe siècle et au-delà, elle incarne l’amour passionnel. La simple vue de sa longue chevelure blonde avait le pouvoir de charmer en un instant les hommes qui l’apercevaient. Apollinaire a choisi cette figure maléfique de la femme trop belle à une époque de sa vie que plusieurs déceptions amoureuses ont marqué par la souffrance. La lecture de son recueil intitulé Alcools donne cependant le sentiment d’une œuvre solaire. « Mon âme au soleil se dévêt », dit-il dans un autre de ses poèmes. Le fond jaune et chaud de la photographie, autre blondeur, est là pour le rappeler. Il tend opportunément à se confondre avec la teinte familière du papier vieilli. Lui aussi semble produire une chaleur, celle de l’amitié que l’on peut ressentir pour Apolli- naire quand on est tombé sous le charme de sa poésie.

The Questioning of the Turned Page

The book is photographed a second time, after turning a page, to show the poem in its entirety. When the reading of one page ends, and before another appears and the words begin again, a moment of silence must be crossed. We are hardly aware of it, but this interstice is visited by our mind. In the composition, a mental space opens in the background of the book and another blue page appears. As a projection of the reader, it is larger. For a brief moment, the reader can see the golden hair of Bacharach’s witch, Apollinaire’s Lorelei. The reader’s thoughts pierce the blue ether to reach what lies beneath and the word “blonde” appears in yellow letters. Thus an additional affinity between the reader and the poem can be established. Guillaume Apollinaire was one of the first poets to abolish punctuation. He placed intelligence in brackets. Above all, he speaks of the impulses of the heart and the despair that leads to them. Love, death. The reader approaches the moment when the page is turned without having to suffer the brakes of full stops or commas. He is carried away by an uninterrupted flow of emotions, which are even more persistent in the period before the first words on the next page are read. This is what justified this poet’s choice to address the idea of an additional, invisible blue page. The Lorelei who inspires Apollinaire in one of his most endearing poems is originally a mythical figure from Germanic folklore. She is a water nymph, a nixe, a kind of mermaid who bewitches sailors and makes them capsise in the Rhine. In the literature of the 19th century and beyond, she embodies passionate love. The mere sight of her long blonde hair had the power to charm in an instant the men who saw her. Apollinaire chose this evil figure of the too beautiful woman at a time in his life when several disappointments in love were marked by suffering. Reading his collection Alcohols, however, gives the impression of a luminous work. In another of his poems, he says: “My soul in the sun is undressed”. The warm yellow background of the photograph, another blond, is there to remind us of this. It tends to merge opportunely with the familiar shade of the aged paper. It too seems to produce a warmth, the warmth of the friendship that one can feel for Apollinaire when one has fallen under the spell of his poetry. >>> Back