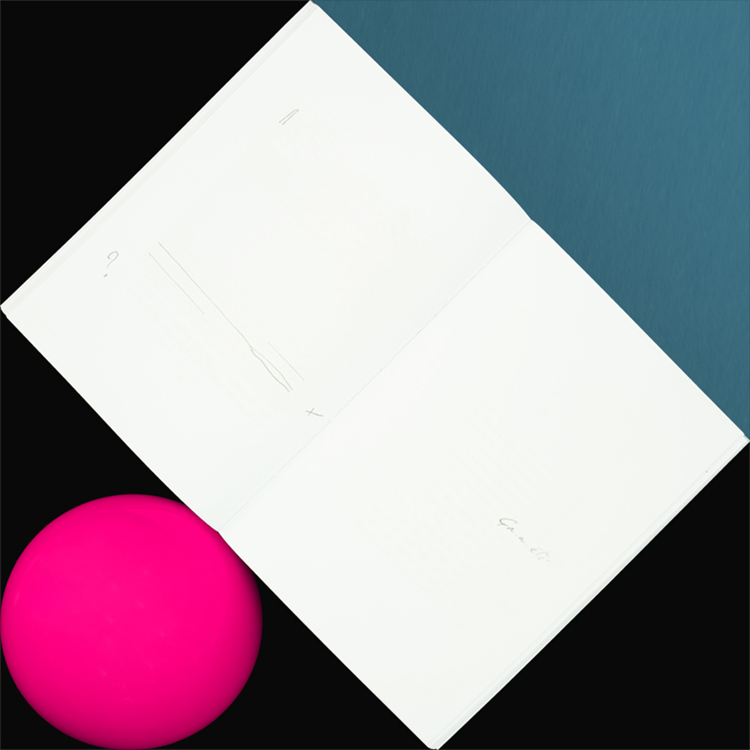

Roland Barthes, La chambre claire

64 x 64 cm - 2021

Lumière de la mort

Il est impossible de cerner l’essence de La Chambre claire sans évoquer la mort de l’auteur. Et cela au moins pour trois motifs auxquels cette composition photographique donne une représentation formelle. D’abord parce que son livre est le dernier et que Barthes va bientôt mourir, un mois seule- ment après sa parution. Trois ans après la disparition de sa mère, Barthes demeurait inconsolable. Le fils avait pour sa mère une véritable vénération, au point que sa force créatrice lui doit beaucoup. « Mam est présente dans tout ce que j’ai écrit », confesse-t-il. Et davantage encore dans La Chambre claire où il parle longuement d’une photo de sa mère prise quand elle avait cinq ans. Tout le texte s’articule autour d’un avant et d’un après la vision de cette photographie. De sa mère disparue, il dira « J’ai perdu la raison de ma vie ». Sans doute aussi le goût de vivre. Explicite, Jacques Derrida écrit « le temps si singulier de ce livre veille étrangement sur la mort à venir de l’auteur ». La sphère rose dans la composition représente cette relation fusionnelle entre Barthes et sa mère. Elle sert de point d’appui au livre dans un axe transversal qui aboutit au triangle bleu qui donne cette forme abstraite à l’acte de penser. Tel une flèche, il pointe en haut à droite, sens naturel d’une action en devenir. En second lieu, il est patent que la mort habite tout le texte de La Chambre claire. Barthes souligne qu’en figeant dans une image le moment de la photographie, le sujet transformé en objet meurt aussitôt. Et si une personne photographiée n’est pas encore décédée, sa disparition future n’en n’est pas moins annoncée et déjà certaine. Être photographié fait vivre « une micro-expérience de la mort », dénonce Barthes. Il témoigne de la même réac- tion offusquée devant une photographie : « Cela est mort et cela va mourir », « je frémis (…) d’une catastrophe qui a déjà eu lieu ». La photographie ne peut rien prétendre au-delà du fait que « ça-a-été ». Ce concept célèbre a été copié au crayon pendant la lecture du livre, sur la page de droite. La présence de cette note manuscrite est une trace du besoin qui fut de l’écrire à un moment donné de la lecture. En guise de démonstration, la compréhension de l’idée de mort imma- nente au sujet photographié devient ainsi elle-même un sujet/instant photographié et donc mort. Il faut troisième- ment considérer la notion de la mort nécessaire de l’auteur d’un texte pour le sémiologue qu’est Roland Barthes. Dans un précédent essai intitulé La mort de l’auteur, il postule que l’auteur, relégué au rang de « scripteur », disparaît dans l’ex- périence de la lecture : « la naissance du lecteur doit se payer de la mort de l’auteur ». Car l’interprétation de l’œuvre par le lecteur a la primauté sur tout ce qui est écrit. Barthes explique que vouloir comprendre le texte en s’alimentant de ce que l’on sait ou croit savoir de l’auteur conduit à une impossibi- lité. Il convient de considérer l’auteur comme mort et enterré, c’est-à-dire soustrait au regard, pour vivre authentiquement la lecture de ses écrits. C’est pourquoi, dans la composition, le texte qui était présent sur la double page a été effacé. Sa position rendue oblique suggère le décalage nécessaire d’un point de vue. Cette absence du texte est la manifestation de la mort de l’auteur telle qu’il était possible de la faire appa- raître dans une représentation plasticienne. Il ne reste que les traces de soulignements et les quelques mots laissés par le crayon. Ils témoignent de la lecture du texte avec l’espoir avoué qu’ils confèrent à cette image « l’air » du vivant. Auquel cas, peut-être, le « spectator » de ma photographie s’écriera « c’est çà ! ». Ce serait reprendre les termes de Roland Barthes quand il parle de cette photographie de sa mère prise lors- qu’elle était enfant au Jardin d’hiver, si particulière parce celle-là seulement lui semblait chargée d’une forme de vérité.

Light of Death

It is impossible to define the essence of Camera Lucida without mentioning the author’s death, for at least three reasons, which are formally represented in this photographic composition. First, because his book was his last and Barthes was soon to die, only one month after its publica- tion. Three years after his mother’s death, Barthes remained inconsolable. The son had a real veneration for his mother, to the point that his creative force owed a lot to her. “Mam is present in everything I have written”, he confessed. And even more so in Camera Lucida, where he talks at length about a photo of his mother taken when she was five years old. The whole text is structured around a before and after vision of this photograph. Of his missing mother, he says, “I have lost the reason for my life”. No doubt also the taste for life. Explicitly, Jacques Derrida writes, “the singular time of this book strangely watches over the author’s death to come”. The pink sphere in the composition represents this fusional relationship between Barthes and his mother. It serves as a fulcrum for the book in a transversal axis which leads to the blue triangle that gives this abstract form to the act of thinking. Like an arrow, it points to the top right, the natural direction of an action in progress. Second, it is clear that death inhabits the entire text of Camera Lucida. Barthes points out that by freezing the moment of the photograph in an image, the subject transformed into an object imme- diately dies. And if a person photographed is not yet dead, his or her future disappearance is nonetheless announced and already certain. To be photographed is to live “a micro- experience of death”, Barthes denounces. He testifies to the same offended reaction to a photograph: “This is dead and this is going to die”, “I shudder (...) at a catastrophe that has already taken place”. The photograph can claim nothing beyond the fact that “it has been”. This famous concept was copied in pencil while reading the book, on the right-hand page. The presence of this handwritten note is a trace of the need to write this down at some point in the reading. As a demonstration, the understanding of the idea of death immanent to the photographed subject thus becomes itself a photographed and thus dead subject/instant. Third, we must reflect on the idea of the necessary death of the author of a text by the semiologist Roland Barthes. In an earlier essay entitled The Death of the Author, he postulated that the author, relegated to the rank of “scriptor”, disappears in the experience of reading: “the birth of the reader must be paid with the death of the author”. For the reader’s interpre- tation of the work takes precedence over everything that is written. Barthes explained that wanting to understand the text by feeding on what we know or think we know about the author leads to an impossibility. One must consider the author as dead and buried – that is, removed from view – in order to authentically experience the reading of his writings. This is why, in the composition, the text that was present on the double page has been erased. Its oblique position suggests the necessary shift in perspective. This absence of the text is the manifestation of the author’s death, in a plastic representation. All that remains are the traces of underlining and the few words left by the pencil. They bear witness to the reading of the text with the avowed hope that they give this image the “air” of life. In which case, perhaps, the “spectator” of my photograph will cry out “that’s it! This would be to borrow the words of Roland Barthes, when he speaks of this photograph of his mother taken when she was a child in the Winter Garden, so particular because only this one seemed to him to be charged with a form of truth. >>> Back