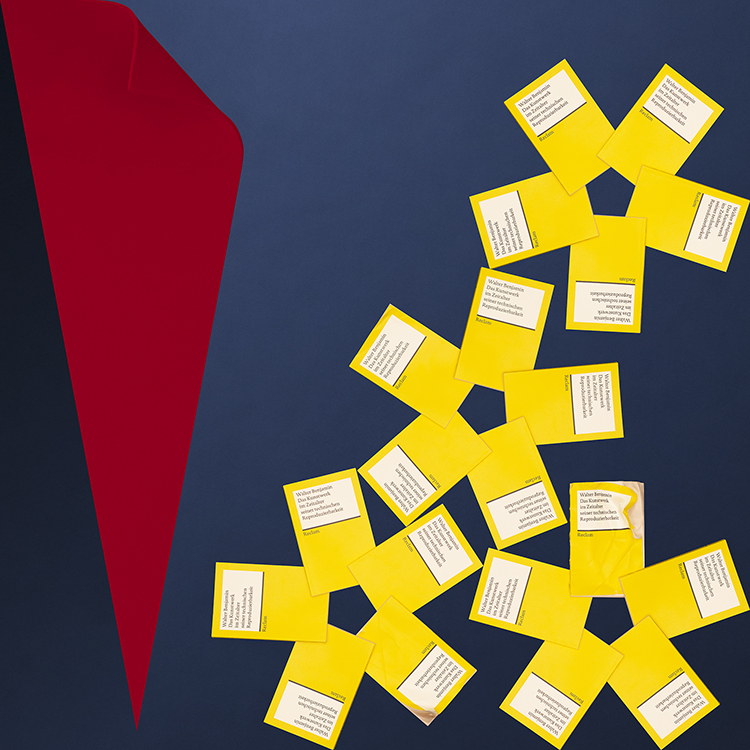

Walter Benjamin, Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit

122 x 122 cm - 2016

L’aura sans Warhol

Il s’agit ici d’évoquer la souffrance morale qu’évoque Walter Benjamin face au dépérissement de l’aura des œuvres d’art que cause la reproduction photographique de leurs représentations. Celles-ci perdent leur unicité et il parle de « catastrophe » pour décrire l’évacuation de l’authenticité qui les caractérisait. La photographie montre cette opposition entre aura et sérialité. Un grand triangle isocèle pointe vers le bas pour indiquer un « ici-et-maintenant ». Cet « hic et nunc » est la condition d’existence de l’aura pour Walter Benjamin qui la définit comme une « apparition unique d’un lointain, si proche soit-il ». La couleur rouge et chaude véhicule la sensa- tion de vérité que produit l’évocation du sang. La pointe du triangle ne touche pas le sol. Il semble flotter comme libéré des lois de la gravité. Il est dans la sphère mentale du sacré, ce qui est bien l’expression d’un lointain. L’angle supérieur droit est relevé et laisse se diffuser lentement une subtile clarté. Cette clarté ne constitue pas une onde lumineuse qui répondrait aux lois de la physique. Il s’agit plutôt d’une matière de pensée qui, telle un liquide bleu visqueux, dont la lumino- sité se dilue en fonction de la distance de sa source. Ainsi, la clarté passe sous la pointe inférieure du triangle avant de se dissiper plus haut, à gauche, c’est à dire dans l’obscu- rité du moment qui précède le « hic et nunc ». A droite, après que soit marquée une distanciation, c’est à dire une dicho- tomie, apparaissent quatre fleurs jaunes dont les pétales sont constitués par cinq éditions identiques de L’œuvre d’art à l’époque de sa reproductibilité technique. Le livre de Benjamin manifeste ainsi la notion de sérialité dont le philo- sophe annonce l’avènement dans l’histoire de l’art. Il faut y voir une évocation directe des sérigraphies d’Andy Warhol intitulées Flowers. En s’adressant aux masses, en faisant des icônes des images de la vie quotidienne et par la pratique des tirages en séries, Warhol fait volontairement disparaître les notions de lointain et d’unicité qui caractérisent l’aura benja- minienne. Dans la présente photographie, il apparaît que la confrontation entre aura et sérialité a produit un choc. C’est pourquoi les quatre fleurs sont bousculées et repoussées dans la partie droite de la composition, là où se situe le futur par rapport au moment où Benjamin écrit son livre. Contrai- rement au triangle rouge, les fleurs jaunes sont soumises aux lois de la gravité. Elles se superposent dans une mise en équilibre compliquée à l’image d’une mécanique à la fois délicate et absurde. Cette approche différenciée de la gravité est une façon de signifier le passage du sacré à la technicité. La position chaotique des fleurs jaunes montre que Walter Benjamin aura vécu son époque comme une chute. Avec pour conséquence un certain désordre qui caractérise aussi bien sa pensée que son caractère porté aux moments de dépression. Si les quatre fleurs jaunes sont constituées des cinq mêmes exemplaires du livre, l’un d’eux subit cependant une entropie rendue visible par le froissement progressif de sa couverture. Cette blessure du livre s’aggrave au fur et à mesure que la matière d’ombre bleue se concentre dans le coin inférieur droit de la composition pour prendre la direc- tion d’un futur inquiétant. Rédigé entre les deux guerres, le développement technique qui crée un tournant dans l’his- toire de l’art et marque les conflits armés plonge l’auteur dans un profond désarroi. Bientôt, il préférera se donner la mort pour échapper à cette violence nazie qui prétend « liquider l’aura » pour « esthétiser la guerre ». Le désir abandonné de retrouver l’aura perdue est ici la vérité fondamentale du livre dont il s’agit de donner la représentation. La représentation de l’aura benjaminienne dans une photographie destinée à un tirage multiple peut paraître paradoxale, voire probléma- tique. Pourtant, il existe des affinités entre le mode de pensée de Walter Benjamin et la démarche sur laquelle est basée l’élaboration de cette composition photographique. D’abord parce qu’il y a sans doute de l’aura qui se dégage d’un livre, objet potentiellement sacré, porteur d’authenticité, unique pour son lecteur et présent à lui seul dans sa lecture. Et cette puissance d’évocation – ou aura – d’un livre quand sa valeur perçue comme capitale dépasse la réalité matérielle du tirage photographique.

The Aura without Warhol

The point here is to evoke the moral suffering that Walter Benjamin evokes in the face of the loss of the aura of works of art caused by the photographic reproduction of their representations. They lose their uniqueness and he speaks of a “catastrophe” to describe the evacuation of the authen- ticity which characterized them. The photograph shows this opposition between aura and seriality. A large isosceles triangle points downwards to indicate a “here-and-now”. This “hic et nunc” is the condition of the aura’s existence for Walter Benjamin, who defines it as a “unique appearance of a distant, however close”. The warm red colour conveys the sensation of truth produced by the evocation of blood. The tip of the triangle does not touch the ground. It seems to float as if freed from the laws of gravity. It is in the mental sphere of the sacred, which is indeed an expression of a distant future. The upper right angle is raised and slowly lets a subtle clarity diffuse. This clarity is not a light wave that would respond to the laws of physics. It is rather a matter of thought which, like a viscous blue liquid, dilutes in brightness according to the distance from its source. Thus, the brightness passes under the lower point of the triangle before dissipating higher up, on the left; that is to say in the darkness of the moment which precedes the “hic et nunc”. On the right, after a segregation, i.e. a dichotomy, is marked, four yellow flowers appear, the petals of which consist of five identical editions of The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin’s book thus manifests the notion of serialism that the philos- opher heralds in the history of art. It is a direct reference to Andy Warhol’s Flowers silkscreens. By appealing to the masses, by making icons into images of everyday life and by the practice of serial printing, Warhol deliberately dispels the notions of remoteness and uniqueness that characterise the Benjaminian aura. In the present photograph, it appears that the confrontation between aura and seriality has produced a shock. For this reason, the four flowers are pushed back to the right-hand side of the composition, where the future is situated in relation to the time when Benjamin wrote his book. Unlike the red triangle, the yellow flowers are subject to the laws of gravity. They are superimposed in a compli- cated balancing act which resembles a delicate and absurd mechanism. This differentiated approach to gravity is a way of signifying the passage from the sacred to the technical. The chaotic position of the yellow flowers shows that Walter Benjamin experienced his era as a fall. The result is a certain disorder which characterises both his thought and his char- acter, prone to moments of depression. Although the four yellow flowers are made up of the same five copies of the book, one of them undergoes an entropy made visible in the progressive crumpling of its cover. This wounding of the book worsens as the blue shadow material concentrates in the lower right-hand corner of the composition, taking on the direction of a disturbing future. Written between the two wars, the technical developments that created a turning point in the history of art, marked the armed conflicts which plunged the author into profound disarray. He soon preferred to kill himself to escape the Nazi violence that claimed to “liquidate the aura” in order to “aestheticize the war”. The abandoned desire to find the lost aura is the fundamental truth of the book, the representation of which is at stake. The representation of Benjamin’s aura in a photograph intended for multiple printing may seem paradoxical, even problem- atic. Yet there are affinities between Walter Benjamin’s way of thinking and the approach on which this photographic composition is based. Firstly, because there is undoubtedly an aura which emanates from a book, a potentially sacred object, a bearer of authenticity, unique to its reader and present to him alone in its reading. And this evocative power – or aura – of a book when its value is perceived as capital exceeds the material reality of the photographic print. >>> Back