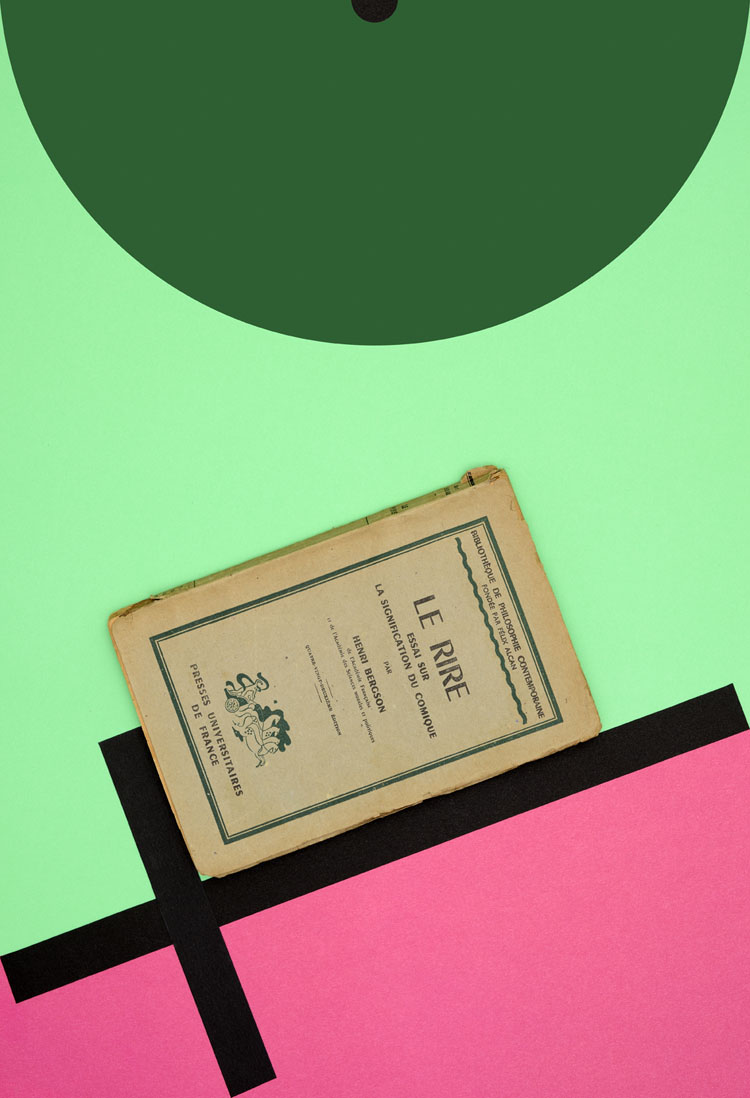

Bergson, Le Rire

80 x 69 cm - 2012

Le rire de Dieu

Chez Bergson, le rire apparaît lorsque l’acte humain s’écarte de ses obligations vitales, lesquelles imposent l’insertion du corps dans le mouvement naturel. La manifestation d’une raideur vient en contradiction d’une souplesse qui devrait épouser l’élan de la vie. Elle s’affiche de façon subite comme un mouvement mécanique anormalement plaqué sur du vivant. Et cet événement est par essence risible, explique Bergson. Dans cette composition, le poids du livre pèse sur une croix. Celle-ci devrait être entrainée dans un mouvement de rotation. Mais s’agissant d’une croix chrétienne, une de ses branches est trop longue et la mécanique se bloque. Elle bute sur le bord de l’image et ne peut plus tourner. La croix est posée sur une pente ascendante évocatrice de l’élan vital bergso- nien. Elle suit une ligne qui sépare un espace vert, propre à l’espérance et au spirituel, et un espace rose, propre au vivant quand le rouge sang se teinte du blanc de l’interrogation intel- lectuelle. Dans L’évolution créatrice, son ouvrage central, Henri Bergson exclut l’idée finaliste postulant que l’évolution suit un plan que Dieu aurait pu initialement lui donner. Pour lui, l’évolution est fondamentalement imprévisible. Le vivant est souple, non pas tributaire d’un inexorable enchaînement de causes et d’effets. L’évolution suit les mouvements d’un « monde qui va à l’aventure ». S’il s’intéresse aux mystiques qui font l’expérience objective de la spiritualité, Dieu reste pour Bergson un inconnaissable. Et donc, si la christianité de la croix, représentée par cette branche longue qui cause un blocage, apparaît ici comme la cause d’une raideur sur le fil de l’élan vital, c’est afin de poser la question de la spiritua- lité chez Bergson. Si l’on suit la logique de la thèse contenue dans Le Rire, l’affirmation d’un rapport entre le vivant et Dieu devrait évoquer une forme de raideur mécanique. Car Dieu est hors du vivant pour Bergson. Alors pourquoi la religion ne fait-elle pas rire ? Sans doute parce que Dieu, représenté dans cette photographie par un cercle vert doté d’un noyau noir, ne se révélant à l’homme qu’à moitié, nous observe peut- être. Représenté sous cette forme, Dieu est à moitié là. Et cela suscite une inquiétude peu propice à l’hilarité. Autant dire que le doute et l’inconnaissance sont le propre de l’homme lorsqu’il épouse, sans raideur aucune, le mouvement vers l’in- connu de l’élan vital. Quant à savoir si Dieu rit de l’homme…

The Laughter of

For Bergson, laughter appears when the human act devi- ates from its vital obligations, which impose the insertion of the body into the natural movement. The manifestation of stiffness contradicts the suppleness that should follow the momentum of life. It suddenly appears as a mechanical movement, abnormally placed on a living thing. This event is in essence laughable, explains Bergson. In the composition, the weight of the book weighs on a cross. The latter should be driven in a rotational movement, but since it is a Christian cross, one of its branches is too long and the mechanism jams. It stumbles over the edge of the image and can no longer turn. The cross is placed on an ascending slope evocative of the Bergsonian vital momentum. It follows a line that separates a green space, proper to the hope and the spiritual, and a pink space, proper to the living, when blood red is tinged with the white of intellectual questioning. In Creative Evolution, his central work, Henri Bergson excludes the finalist idea that evolution follows the plan that God might have initially given it. For him, evolution is fundamen- tally unpredictable. Living things are flexible, not dependent on an inexorable chain of cause and effect. Evolution follows the movements of a “world that goes on adventures”. While he is interested in mystics who experience spirituality objec- tively, God remains for Bergson an unknowable. And so, if the Christianity of the cross, represented by this long branch that causes a blockage, appears here as the cause of a stiff- ness on the thread of the vital impulse, it is in order to pose the question of spirituality in Bergson. If we follow the logic of the thesis contained in Laughter, the affirmation of a rela- tionship between the living and God should evoke a form of mechanical stiffness. For God is outside the living for Bergson. So why does religion not make us laugh? Probably because God, represented in this photograph by a green circle with a black core, only half revealing himself to man, is perhaps watching us. God is half there. And this gives rise to an uneasiness that is not conducive to hilarity. One might as well say that doubt and unknowing are the hallmarks of man when he embraces, without any stiffness, the movement towards the unknown of the vital impulse. As to whether God laughs at man… >>> Back